Incentivizing ADU Development - A Proven Housing Solution for Cities & States

A market based approach to accelerate housing development is possible.

Where's the evidence?

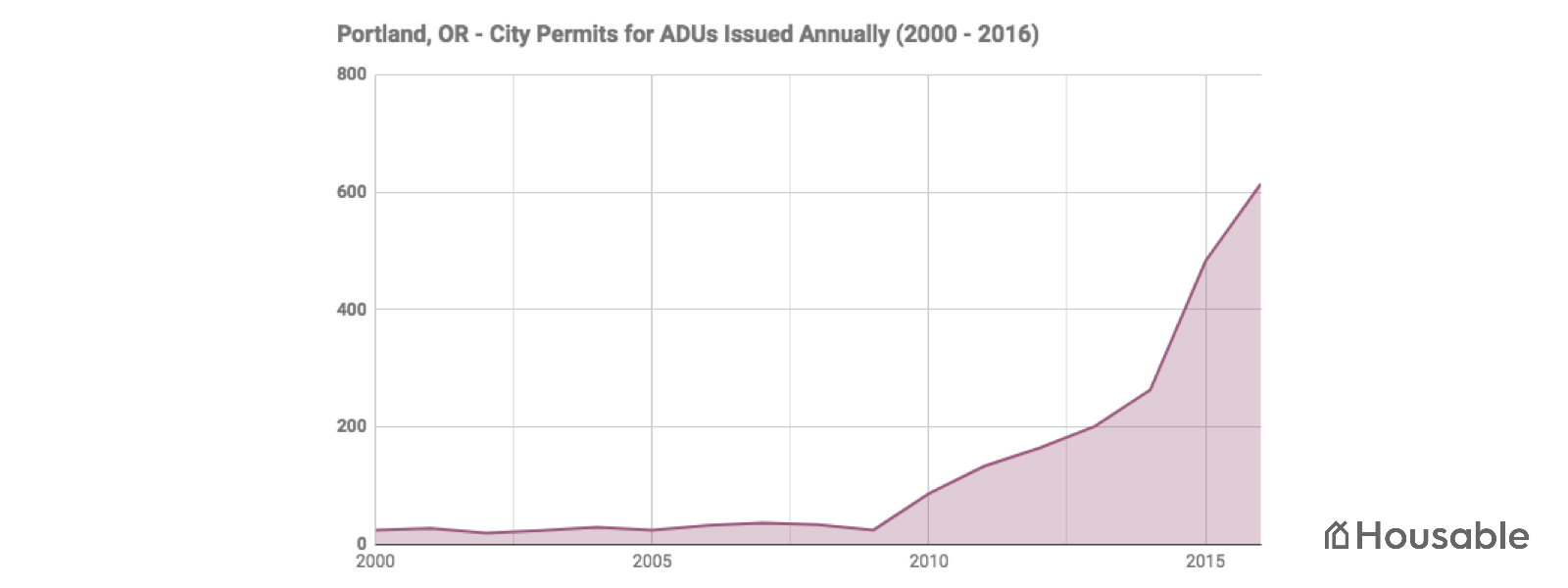

In response to the financial crisis in 2009, The City of Portland took up bold steps to develop affordable housing in the city by incentivizing homeowners to build Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), more commonly known as granny flats and basement apartments. Eight years later, it’s clear this program has turned out to be a more powerful force in the city’s housing market than nearly anyone thought was possible.

By educating their citizens and waiving costly permit fees for their development, the city’s production of ADUs has risen more than 20 fold from about 30 per year pre 2010 to just over 600 units last year. What’s more impressive, this shows that in just eight short years, when compared with primary single family homes, the city has nearly doubled it’s annual housing production. - There were around 800 permits for SFRs issued in 2016 in Portland.

Portland’s housing market as a whole has recovered faster and stronger than average which has caused rents to zoom past record highs. Portland faces similar challenges to those of the Bay Area and Los Angeles, but has carved out a promising long term solution by rapidly increasing ADU production. By recognizing that income investment potential is a financial boon for homeowners the city has catalyzed the creation of a entirely new market by simply educating and incentivizing. Digging in to the details shows the success of this program more clearly. This chart shows the growth ADU permits issued annually in Portland. It’s been hockey stick growth ever since the program was first approved in 2009.

The steps the city took to incentivize ADUs were simple, which probably deserves much of the credit for their effectiveness.

- Temporarily reduce the total cost to permit an ADU by suspending systems development charges, which are typically to $8,000 to $13,000.

- Take actions to educate homeowners about their eligibility to develop ADUs and what the benefits are. Also making clear that the new fee waivers were being made available on a temporary basis. (Though it has since been extended twice since its original implementation and is expected to continue it further based on its widespread success.)

- ADU development can be rapidly accelerated when homeowners are educated and properly incentivized.

- There is not any demonstrable limitation to the impact this approach can have other than the total number of eligible homeowners and how quickly they can be convinced to take action to build ADUs.

In total, there have been over 1,900 permits have been issued since the start of the program in 2010 - A drop in the bucket compared to the potential long term impact for the city. Less than 2% of the estimated 148,000 single family residential properties in Portland that could add a second unit currently have one. The city’s long term goal is for ADUs to exceed 10% of all housing supply.

On their own, these results are impressive, but they bring up larger questions - How much impact can ADUs have? What is the upper limit? How many of the eligible homeowners would actually consider adding a second unit to their property?

Fortunately, answers to these questions may be found by looking to another pioneering Northwestern city…

Where is the upper limit?

Enter Vancouver, BC - The Canadian city’s homeowners have supplemented housing supply with the development of ADUs for more than four decades. Locally referred to as “Laneways”, Vancouver homeowners began adding ADUs at a steady pace back in the 1970s to increase density in response to rising housing costs. Fast forward to today, with about 75,000 single family residences in the city, over 26,000 (35%) have a permitted ADU.

Even at this level of penetration, the market still sees no sign of slowing down. The city is currently permitting about 1,000 units per year, a 1.3% addition to it’s total housing stock annually.

One neighborhood in Vancouver, the Kitsilano District, was originally developed in the 1920s with two and three bed, single bath homes. The community was designed then for density of about 6.5 dwellings per acre. Fast forward to the 1990s, and thanks to laneways, garage conversions and basement units, this same neighborhood boasts more than twice the original density at 13.4 dwellings per acre.

Both Vancouver and Portland provide us with proven models for understanding the short run and the long run impact that supportive zoning policies for ADUs can have on the production of new housing in cities.

California is showing signs of promise, but more must be done.

California has been in the midst of a housing crisis and many feel that the state has been slow to take action, let alone bold, decisive policies to solve it. This is uncharacteristic of a state which is on the cutting edge in so many fields both socially and economically. With more than six and a half million single family homes, California has the opportunity to take the programs demonstrated by Portland and Vancouver to a new scale and get on a path to addressing it’s housing shortfall in the process.

Recently though, demonstrable progress has been underway. Last year, the State Legislature passed legislation, SB1069 and SB 2299 to mandate that all local governments incorporate ADUs into their zoning codes according to a set of minimum set of standards. These standards now make ADUs a “by-right” choice for millions of single family homeowners in California.

To say that state policy makers have been totally unaware of the potential for ADUs to become a real housing solution until recently is actually not a fair statement. Believe it or not, California has had legislation on the books encouraging cities to allow ADUs since the early 1990s. Unfortunately though, because it was not widely communicated or enforced, it has had virtually zero impact in furthering ADUs in the state. Looking at this past legislation reveals that the new mandates currently being implemented by all cities in California are really just extension of this earlier bill, but set up to be minimum standards not simply guidelines.

This may show just how important it is for government to play a more active role in finding the solution to housing this time around. The need is greater than ever, and we cannot expect optional guidelines to be implemented with the same speed and conviction as strict mandates. For policy makers and urban planners in California and throughout the country who are grappling to respond to rapidly rising housing costs, looking at both cases in Portland and Vancouver prove a couple fundamental points.

In 100 years, will all single family homes be paired with a second unit? Maybe, maybe not, but the evidence that ADUs can become a larger part of the housing solution not only in the far off future but also today is too compelling to ignore. It is a shame that these policies were not implemented more vigorously back in the 1990s. It is hard to say how many more tens or even hundreds of thousands of homes we would have today as a direct result. That aside, the next best time to act is right now.